from Articles...

Home | A Year of Our Own | Articles | Photography | Bio | Contact

William Baeck: Writing & Photography

London Sings with Many Voices on the First Day of Spring

for the San Antonio Express-News

According to my London friends, June 21 is one of the three days each year you can trust the English weather not to rain or snow on, parboil or bluster across the city’s 7 million inhabitants (the other two days being the Queen’s birthday and the day before you leave on vacation). Thoughtfully, this gentle, wafting day is also the longest of the year. So I wasn’t surprised to wake in London on June 21 feeling like I wanted to sing, and expecting the city to join with me.

And London obliges. Each June 21, the city hosts a free musical event called Exhibition Road Music Day. From 10 a.m. until midnight, musicians from around the world gather in buildings along this major London thoroughfare to perform concerts and present music workshops for free.

Visitors enjoy a before-concert snack in the

Science Museum's futuristic cafeteria

Not one to waste this musical mood, my wife and I left our third-floor Victorian flat in Maida Vale and took the Underground down to the South Kensington station near the bottom of Exhibition Road. Fifteen minutes later, we surfaced from the station like prairie dogs with our London A-Z pocket maps in hand. Blinking fiercely in the noon light, we stood with heads swiveling to get our bearings until a Music Day volunteer handed us a brochure listing the day's events and their locations, gently pointing us in the right direction.

Music Day is not a London invention. It began in 1982 in France as Fête de la Musique, the brainchild of Jack Lang, then French minister of culture. His plan was to have a festival on June 21 celebrating music from around the world. Since then, the Fête de la Musique has grown into an annual event called World Music Day, with countries throughout Europe participating. Recently, several institutions along Exhibition Road, including the Victoria and Albert Museum, the Natural History Museum and Royal Albert Hall have joined in this festival, presenting dozens of free concerts and musical workshops.

Our first stop was the Goethe-Institut at the north end of the road, near Hyde Park. Although the rest of the year this institute is a learning center promoting Germany’s language, politics and culture, today it was promoting world culture. Leaving the large and busy street, we were ushered through the rear of the institute onto a large lawn.

Visitors enjoy world music at the Goethe-Institut.

It was as if we’d stepped straight home to a backyard barbecue. A cook grilled lunch on the wooden deck. Guests sipped wine beneath trees, while old friends got loudly reacquainted over burgers and beer, waiting for the next band to finish setting up on a stage placed against the back of the institute. It was a perfect example of the difference between public and private London: brisk formality on the outside, but an astonishing warmth and friendliness once we were invited ‘round back.

We found a comfortable spot on the grass, and listened first to a jazz band flown in from the Continent, with two women trading leads in a vocal jam session, followed by an instrumental group from Brazil, with keyboard, upright bass, snare drum and bongo sending looping, polyrhythmic sambas into the spring air.

It was lovely, but after a while, the scent of hamburgers grew stronger than the music, as did the sounds coming from my rumbling stomach. The Goethe-Institut has its own restaurant, called Hugo’s Café, so we decided on a sit-down meal instead of burgers on the lawn. Institutional food too often tastes like it was made out of old exhibits, but at Hugo’s we ordered an excellent pair of vegetarian dishes made from organic rice, noodles and crisp veggies.

After lunch, we looked over the list of events. This was when my wife pointed out that the concerts were spread along a half-mile section of road. We realized we not only needed to plan whom we wanted to hear, but where they were performing. Otherwise, Music Day was going to be a combination music festival/aerobic workout.

It looked like there was a theremin recital at the Science Museum in 15 minutes that we could just make. Theremin, the instrument that provided the soundtrack to a hundred science fiction movies in the ‘50s; this should be interesting, I thought.

Out we went, back onto Exhibition Road, all concrete and sunshine, across the street, and down to the Science Museum a block away. Getting to any large museum in London is the easy part, as you’re unlikely to miss a building roughly the size of the mothership in Independence Day. The problem is finding the right exhibit once you're inside. Many of the items in the exhibits were discovered by 19th-century explorers, and it takes similar navigational skill to locate the collections within these large and complex museums.

Making our way across the vast marble floe of lobby, I asked a woman behind the information desk where the theremin concert was being held. The answer was what I'd feared. “Head to the far side,” she said in the same imperious voice that had once swayed empires, “avoiding the V2 rocket” (always good advice). “Then take the lift to the third floor galleries” (“elevator to the fourth floor” for us Americans), “make your way through Optics, and stop just past Marey's zoetrope” (which, it turned out, was an early moving picture viewer, not the extinct species of giraffe I’d expected).

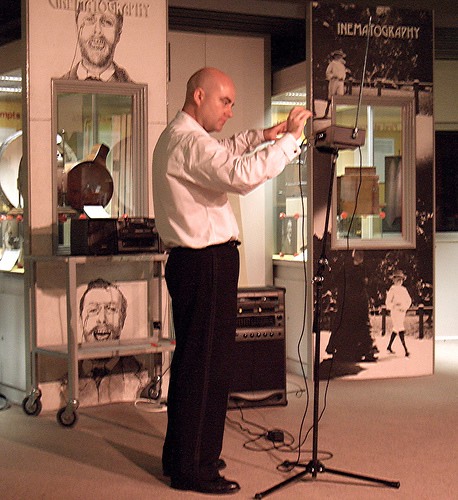

And simple as that, we were in the Cinematography Gallery, and there, bolted atop a microphone stand was a theremin — a slender wooden shoebox filled with electronics and fitted with dials, a loop of antenna sticking horizontally out the left side and what appeared to be a car aerial pointing skyward from the right side. It looked like something Baron von Frankenstein would have played in the laboratory to pass the time between lightning storms.

The performer was an affable man with a shaved head and dark eyes roofed with heavy eyebrows. He briefly explained that the theremin was invented by a 22-year-old Russian physicist named Léon Theremin in 1919. The box generated a signal controlled by the antennas, and this signal went to the small guitar amplifier by the performer’s side. His shaved head then tilted thoughtfully, the eyebrows lofted upward, and he began playing, waving his hands in the air in front of the theremin, like a conductor at a podium.

A musician guides his hands over the theremin's antennae to play it.

The theremin is the only instrument I know that is played without making physical contact. By moving his left hand toward the horizontal antenna he controlled the volume, while moving his right hand toward the vertical antenna changed the pitch, though he never touched either. But this untouchable quality also made it an instrument of the imagination. He had to suggest to the theremin what sounds it should create, shaping notes literally out of the air. What came from the amplifier was ethereal, with a cello-like lower register, changing to a violin in the middle range, and at the high notes, vocalizing uncannily like a soprano. The sound was like something from Intergalactic Music Day.

Coming back to earth, there was still time for us to hear a Celtic folk duo followed by a traditional English folksinger at the Institut Français du Royaume-Uni. The French equivalent of the Goethe-Institut, this institution is housed in an art deco building off the south end of Exhibition Road. It even has its own competing restaurant, Le Bistrot, where afterwards, we — I was about to say “enjoyed” but perhaps simply “drank” is the more honest word — complimentary Ricard aperitifs.

By now it was time to return to the station. Rounding the end of Exhibition Road, I could see members of the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra leading a free drumming workshop on the front lawn of the Natural History Museum. A dozen young men stood in a wide circle, several of them stripped to the waist in the warmth of late afternoon sun. Placed like an enormous wooden goblet before each was a tall wooden drum. The tableau was familiar.

That’s because I’d seen something like it once, years before, on my first trip to England. My wife and I had been driving through the Salisbury countryside southwest of London just before sunset. As we topped a low hill, we saw the immense circular outcrop of stones that marks the ruins of Stonehenge.

Perhaps it was just the similar shape both groups made, the columns of stones that day and these drummers on this. Maybe it was that June 21 marks the summer solstice, the end of spring, and there was the sense of the ceremonial and the primitive about each.

But the connection might have been more than mere simile. I couldn’t help wondering whether an ancestor of one of these drummers, a hundred generations earlier, had marked the solstice in a similar way at Stonehenge.

From Theremin to Stonehenge on the nicest day of the year. No wonder I felt like singing.

Previous Article | Next Article

© 2010 William Baeck. All Rights Reserved