from Articles...

Home | A Year of Our Own | Articles | Photography | Bio | Contact

William Baeck: Writing & Photography

Death in the West:

California’s Ghosts

for the Contra Costa TImes

A dead town and a dying lake are the liveliest spots along this lonesome stretch of California highway. And despite how that sounds, together they make for a great day of exploring near Yosemite.

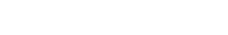

Visitors wander up Green Street in Bodie

Bodie is the largest and best-preserved ghost town in California, a classic example of Gold Rush boom and bust. Founded by William S. Bodey in 1859 after he discovered gold in the nearby hills, the town grew from an initial population of 20 miners to some 10,000 residents by 1880. But 50 years later it was all over — the mines played out and most of the buildings destroyed by a fire that swept through Bodie in 1932.

A rough town, inhabited by miners, gamblers, prostitutes and those who lived off them, Bodie was a nasty place even on a good day. And with homicides a regular event, there were few good days in Bodie. “Goodbye God, I’m going to Bodie,” read one young girl's diary entry on learning her family was moving there.

Located high in the Eastern Sierra, Bodie is hot in summer and freezing in winter. Since it was going to be a warm day when I visited, I decided to go in the relative cool of the morning and bring plenty of water. Turning off Highway 395, I drove 10 miles east on Highway 270 until the paved road ran out. Then it was three more bumpy miles up a gravel track that ended at the edge of Bodie, 8,400 feet above sea level.

Just as it was

The town is made up of 170 surviving buildings spread over 500 acres. Since 1962 this national historic landmark has been preserved as its last residents left it, in a state of arrested decay, from the Methodist church near the parking lot to Dog-Face George’s house a third of a mile away. Most of the dwellings are unpainted shacks, many tipped by age into odd angles. The overall effect is of a town dropped from the same tornado that landed Dorothy in Oz.

One shack is reflected in the window of another.

I stepped onto a creaking front porch and through an open door to see inside one of the houses. The first thing I noticed was the smell. Bodie’s houses smell of baked dirt and raw wood.

Surprisingly, some still contain their original furniture, with tiny bed frames and rocking chairs pocketed into corners where the owners abandoned them in the early 1930s. Floral wallpaper peels from walls, remnants of a colorful touch once given to these cramped rooms.

Meanwhile the public buildings provide an idea of Bodie’s business life. The main shop in town, the Boone Store & Warehouse, is still stocked with goods. A tall, ornate display of Guittard & Co. coffee stands front and center. Shelves of patent medicines line the walls — whatever they promised to cure faded with age.

Warehouse shows it’s still well-stocked.

Around the corner, the Miner’s Union Hall now serves as a museum and gift shop. After looking at the memorabilia there, I eavesdropped while the cashier told a visitor about the town’s vigilante group, the Bodie 601 Committee. “What's the number mean?” the man asked. “Six feet under, 0 trials and 1 rope,” the cashier replied.

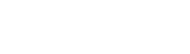

Remembering the ACLU membership card in my back pocket, I thought about what a different world Bodie was, one that I could never have felt part of. But not long ago, one of its inhabitants decided to move back permanently. Bodie’s cemetery, a few hundred feet outside town, is marked by a few Masonic memorials and a wistful marble angel.

A forlorn angel holds vigil in Bodie’s cemetery.

Bodie’s final resident, Robert “Bobby” Bell, returned here to be buried in 2003.

Mono Lake: thirst, tufa

Getting back onto Highway 395, I headed 15 miles south to Lee Vining, about a dozen miles east of Yosemite.

The story of Mono Lake is similar to Bodi’'s: Discovery of a natural resource was followed by exploitation and then abandonment when that resource ran out. But unlike Bodie, Mono Lake is slowly returning to life.

From a distance, Mono Lake looks like an enormous pie tin set in the desert below the roadway — metallic, round, and flat. It’s a terminal lake, meaning there's nowhere for the water to go except by evaporation. The result is that over the eons the lake has accumulated a lot of minerals. It’s more than twice as salty as the ocean, and having tasted it, I can testify that the minerals give the water a bitter taste and an oily feel. But this seemingly inhospitable locale is also the setting for an amazingly rich ecosystem, from brine shrimp and alkali flies to the dozens of varieties of birds that feed on them.

Save Mono Lake

This was an ecosystem that was almost lost.

In 1941 Los Angeles began diverting the freshwater streams that fed Mono Lake to provide water for its thirsty residents. By the 1990s, the water level had dropped 40 feet, doubling the salinity of the lake and threatening the large and complex ecology of the area.

Fortunately, volunteers have worked to change Los Angeles’ water-diversion habits, and Mono Lake is doing better now,

though it's by no means healed.

Like most visitors, what brought me here are the tufa formations that have been exposed by the lowered lake level. These are groups of limestone towers created when underwater springs rich in calcium reacted with carbonates in the lake water.

Because tufa develops underwater, it doesn't form elegant, thin columns like the stalagmites found in caves. Instead it is the stalagmites’ Elephant Man cousin, tumorous and grotesque, but fascinating.

Some of them emerge from the lake as spiky islands of brown and gray. But in several spots the water has receded so much that I could walk among these fragile spires on what is now dry land ringing the lake.

Tufa formations rise from the water in Mono Lake.

Formed three quarters of a million years ago, Mono is a candidate for the oldest lake in the U.S. It certainly looks the part. It seems primitive, prehistoric.

But this alien landscape is temporary.

The water in Mono Lake is rising, slowly returning to its original level. A few decades from now, the tufa will be underwater again and the lake will be healthier. The irony is, it will also be a lot less interesting.

Climbing Panum Crater

A ranger at the visitor center suggested that I finish my visit to Mono Lake by following the trail up Panum Crater, a 650-year-old extinct (I was assured) volcano near the south edge of the lake. The hike took about 90 minutes, round trip.

As I climbed, brush and scree soon gave way to large boulders. Reaching the top, I looked down into the caldera. SUV-sized chunks of volcanic material were piled up dark and glassy in the collapsed cone, as if they’d been shattered out of a giant tray of black ice cubes. It was hard to imagine they’d been liquid once. But up close the signs of cooling were evident, the rock surfaces wrinkled and iridescent, like crumpled silk.

Across the crater’s rim I could see Mono Basin and the surrounding Sierra stretching back toward Bodie. It was a good way to end the day. It gave me perspective.

Panum Crater, Mono Lake, and Bodie are a story of sudden loss — of magma, water, and gold.

And how we appreciate what’s left behind.

Previous Article | Back to Articles

© 2010 William Baeck. All Rights Reserved